John Lennon once sang “Imagine no possessions — I wonder if you can.” After I sold everything I owned and moved out of state, these lyrics represented nearly everyone I met.

“You sold everything you owned? That’s crazy. I could never do that.”

I used to feel the same way. Parting with personal belongings was difficult because I viewed an item’s price tag as a solid representation of its value. I often told myself things like:

I can’t afford to lose that, it’s a — $200 stereo, $500 television, $300 suit.

Incidentally, this materialistic mindset almost cost me my life.

It was the summer of 2000. High school was done. My friends and I celebrated our newfound freedom impractically: We used our savings to buy Jeeps, and then spent most of the summer off-roading. It was during one of our off-roading adventures when we discovered “Gravelly Run.”

Gravelly Run is a hidden water hole in the middle of the Pine Barrens. It served as an alternative to the beach when you wanted to go swimming with the added benefit of no parental supervision. For those who knew about it, Gravelly Run was a haven for teenage rebellion. It also sets the scene for my most notorious moment of indiscretion.

At the start of the summer, Gravelly Run was an ordinary water hole. By summer’s end, resourceful daredevils had transformed it into the most feature-rich water hole in South Jersey. Self-built add-ons appeared every time we went there: A rope swing was hung from a tall tree branch for killer cannonballs. Wooden platforms were attached to trees along the water’s edge for diving. A zip line suspended 30 feet in the air stretched between the opposing shores for a high-rise thrill.

For the uninformed, a zip line is a steel insulated cable with a trolley on it. The trolley has handlebars that you use to “zip” from one end of the cable to the other. Once we saw it, we immediately wanted to try it

out.

Unfortunately, whoever set up the zip line didn’t leave the trolley behind. Without it, the suspended cable loomed high above — clearly teasing us.

Determined to try out the latest addition to Gravelly Run, I improvised: I retrieved a tow rope from my Jeep. It was a 12 foot long piece of sturdy rope with metal hooks on both ends. Convinced this could work, I tucked it under my arm and ran back to the water’s edge.

I climbed the series of two-by-fours that had been nailed into the tree trunk until I reached the zip line. The treetop swayed easily in the summer breeze with me perched in it. Fearlessly, I latched the two

metal hooks onto the insulated steel cable, then planted my bare feet into the center of the “U” I created with the rope. Holding the rope near the hooks, I adjusted my weight from the tree limb to the tow rope

— and committed myself to the ride.

I quickly learned that a tow rope is a poor choice of vessel for crossing a zip line. My weight caused the hooks to dig into the cable insulation. Consequently, the insulation stripped off as I slid down

the cable. It bunched up around the metal hooks in a mess of clear plastic as it peeled.

Eventually, I found myself stranded high above the center of the water pit. The stripped insulation had bunched up to the point where the metal hooks slid no further. I lost my balance and fell 30 feet into

the water below. My tow rope remained firmly embedded in the cable.

I swam ashore, looked at the mess I created, and frowned. Half of the zip line was bare steel cable, half of it was still insulated, and smack in the center was a big knot of plastic that held my tow rope hostage.

I instinctually thought: I can’t afford to lose that, it’s a $50 tow rope.

With this thought, I caused myself to do the stupidest thing I’ve ever done in my life: I attempted to retrieve my tow rope using a makeshift harness made out of towels.

The idea seemed logical when I first imagined it. It seemed logical as I swam to the other side of the water pit holding the towels above my head. It still seemed logical as I climbed the tree with the two towels slung around my neck. It even seemed doable as I sat perched in the tree and tied the towels to the cable.

“Just like in the Cliffhanger movie,” I thought. I foresaw myself sliding along the cable with profound ease while being suspended upside down in the harness. I foresaw everyone on the shore clapping and cheering as I dislodged the tow rope. I did not foresee — or even consider the possibility of — falling 30 feet to my death.

I completed the harness. One towel was wrapped around my back, the other was under my butt. The idea was that the towels would support me as I laid in a horizontal position, and I could wriggle along the cable easily.

The reality, however, was that I wriggled only five feet from the treetop without incident. I gasped in fright when the towel that was previously supporting my butt slipped under my knees. My legs clenched

around the towel hard, and suddenly I understood what might happen if I fell this close to the shore.

I tried to scoot back into the lower towel, but only managed to bunch the higher towel tight beneath my armpits. I heard my friends shout things from the shore as I stared at the sky feeling trapped.

If I had been given more time, I may have thought of trying to return to the tree. My ability to make choices ceased, however, when the knot in the towel supporting my torso untied.

With nothing supporting my torso, I toppled backwards out of the harness. I struck several tree branches during my 30 foot descent and landed in shallow water belly-up. My butt struck the floor hard.

“Are you okay!?” someone from the opposite shore shouted. I waved my arm to signal that I was unharmed, although I hadn’t really assessed whether I was or not. My back hurt, my butt hurt, and I was unable to speak — I was in shock.

If I had landed on the shore, I would have broken bones. If I had landed head first, I would have been paralyzed. If I had landed head first on the shore, I would have died.

Luckily, the worst injuries I received from the fall were a scraped-up back and a bruised butt. More interestingly, I left Gravelly Run that day having learned an important lesson: Life is more valuable than things.

Looking back on that day, I see two things being put on a scale: a tow rope and a human being. One of those things can be replaced for a mere $50. The other, on the other hand, is irreplaceable. From this perspective, it’s easy to tell which is worth more.

Don’t risk your life the way I did in order to learn this lesson. Know that it’s not possible to put a price on the human experience — it’s simply too valuable. When you find yourself facing a choice that could endanger your life, remember to ask yourself: How much is your life worth?

Shaun Boyd is a former computer guy who has reinvented himself as a writer. You can read more of his works at LifeReboot.com.

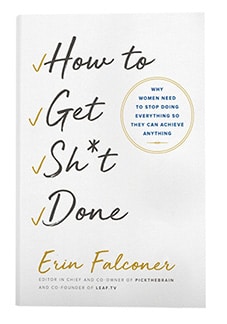

Erin shows overscheduled, overwhelmed women how to do less so that they can achieve more. Traditional productivity books—written by men—barely touch the tangle of cultural pressures that women feel when facing down a to-do list. How to Get Sh*t Done will teach you how to zero in on the three areas of your life where you want to excel, and then it will show you how to off-load, outsource, or just stop giving a damn about the rest.

新しくて高品質の人形は、中古の人形にはない、より楽しくて新しい機能も提供できます。 また、ショップで新品のダッチワイフを購入した場合は、その保証を取得するだけで、保証期間内に問題が発生した場合は製品を交換できます。 ラブドール かわいい

I truly wanted to make a small comment so as to say thanks to you for the nice tactics you are writing at this website. My time intensive internet search has now been paid with pleasant content to share with my friends. Love Doll Blog

에볼루션코리아

171zJwvyD\[.

에볼루션카지노

122xzyOyk{(\

에볼루션바카라

286LCGPNO!>”

에볼루션룰렛

867BusIYT}%&

에볼루션블랙잭177eSYTgI/^$

The best e-cigarette liquid site in Korea. Korea’s lowest-priced 전자담배 액상 사이트 e-cigarette liquid.

스모크밤775 스모크밤

제주룸

361uLBSki+/[

강남사설카지노

707DvwxwX<&%

강남카빠

947hQxHNa#^!